East Syracuse resident was concerned with improving his strength when he visited his urologist

By Aaron Gifford

Dale Russo didn’t notice any warning signs that day he went to the urologist to ask about a testosterone boost.

At 68, Russo’s body was definitely aging, but he could still do 100 pushups every morning.

He wanted to find a way to increase his strength faster than the rate at which he was losing muscle. After a lengthy discussion, the doctor advised that a testosterone injection probably was not the best fit for him.

Russo thanked the doctor for his time and was reaching for his jacket when the doctor made a suggestion. That pause may have saved his life.

“It was by happenstance really,” the East Syracuse resident recalled. “He said, as long as you’re here, why don’t you let me check you.”

This was in November 2018. During the prostate exam that followed, a node was discovered in Russo’s prostate gland. The biopsy two weeks later confirmed what Russo feared: Prostate cancer.

“In the beginning,” Russo said, “that was definitely not what I wanted to hear.”

Luckily, the disease was in the early stages.

The prostate is a gland found only in males. It makes some of the fluid that is part of semen. The prostate typically increases in size as men age. It’s about the size of a walnut in younger men, but can be much larger in older men. According to the American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men, behind skin cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be more than 191,000 new cases in the United States for the year 2020, and more than 33,000 of them will be fatal.

About one in every nine men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during his lifetime, and about one in every 49 men will die from the disease. About six of every 10 cases diagnosed occur in men 65 or older, and the disease is rare in men under 40. The average age at diagnosis is about 66. African-American men are at a higher risk for prostate cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

PSA (prostate-specific antigen) testing is a common method for physicians to monitor aging men for the disease. PSA is a protein made by cells in the prostate gland. It is found in semen, and smaller amounts are found in blood. In blood, PSA is measured in units called nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), according to the American Cancer Society. Doctors may recommend further prostate cancer testing if the patient’s level is above 3.0, though some physicians prefer to establish the threshold at 4.0 ng/mL or higher.

Russo, a local real estate agent who previously worked as an information technology specialist for 30 years, had some decisions to make.

He was leaning toward surgery, but wanted to know all of the options that were available, regardless of how far he had to travel. He talked to patients who fought the same disease, and did not like what he heard about how surgery affected them: Painful recovery, leakage and diminished sexual ability.

Traditional radiation therapy was another option. Russo was told he would require between 30 and 35 visits. He couldn’t imagine juggling that with his full-time job selling properties.

“At that point, all of the choices were pretty rough,” he said. “The problem is, many doctors won’t tell you all of the options that are out there. They only tell you about what they have in their back room.”

Russo continued his research, and came across advertisements for the CyberKnife procedure. At first, it appeared that the nearest available locations were in New York City or Long Island. He was making arrangements to travel to downstate either way when on a whim he performed a second web search, and discovered that the surgery was available just down the road from him in East Syracuse.

“I watched the videos and liked what I saw right away,” he recalled. “Being a computer guy, I liked the idea that it was 100% animated.”

Russo met with physicians at Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York (HOACNY). He signed on for a care plan that involved five sessions with the CyberKnife.

Russo, a self-proclaimed techie and science fiction fan, described his experience as such:

Coordinated MRI and CT scans created a GPS map that the CyberKnife follows with laser precision. The 10-foot tall robot reminded Russo of something out of “Star Wars.” The lights go out, the physicians go into the control room, and the star of the show appears.

“I’m looking up at this thing, and he’s looking down at me. Kind of scary at first, but you never feel a thing,” Russo said. “All you see is this big head zipping around. He even went underneath me and shot upward. We did this every other day for a week, and I was actually looking forward to going back!”

According to HOACNY, CyberKnife is a form of targeted radiation therapy known as SBRT, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. Unlike traditional radiation therapy, SBRT delivers radiation only to the cancerous tissue, sparing the healthy tissue around it, and in much less time.

“The dose it delivers in five treatments is biologically more effective than conventional radiation that takes two months to deliver,” explained physician Shing Chin, a radiation oncologist at HOACNY.

Chin added that the device’s computer-controlled robotics provide the highest level of precision for managing treatment of cancerous tissue, which is vital because the prostate gland can move unpredictably throughout the course of procedures. This tracking system uses tiny pellets made from gold, called fiducial markers, which are inserted into the prostate gland by the urologist several days before treatment begins.

Russo said the after-effects were minimal. He has not experienced any leakage or erectile dysfunction. He was able to immediately work on a part-time basis, and has since returned full time.

Russo acknowledges that he does get tired out in the later afternoon, but is able to recoup after short periods of rest. The only other change he noticed was that alcohol had a stronger effect on him to the point where he can never consume more than two beers in one night.

At the time of his cancer diagnosis, Russo’s PSA was 4.2. Two years later, at the age of 70, his last test was 0.3. He plans to get tested again before the end of this year.

“It’s been a blessing,” Russo says, “but I’ll never underestimate the importance of screening.”

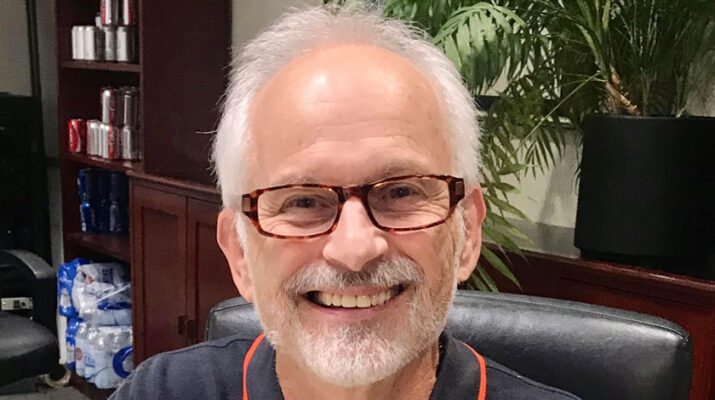

Photo: Dale Russo, 68, of E. Syracuse.