Contact tracers say in many ways, they are like old-fashioned detectives

By Payne Horning

Researchers at Columbia University recently released a study indicating how effective measures to enforce social distancing and restrict individual contact have been in the United States’ battle with COVID-19.

The analysis suggests that these steps reduced transmission rates and thus the overall death rate.

In fact, the model used in the study showed that had the country’s leaders implemented these social distancing measures just one week earlier — on March 8 rather than March 15 — as many as 36,000 deaths could have been avoided, which is more than one-third of total deaths related to the virus in the U.S. to date.

Key to the success of the social distancing initiative is a group known as contact tracers.

Contact tracing is the practice of tracking down people who have either tested positive for the virus or those who have come into contact with someone who is infected.

Like the roots of a plant, the contacts one person has can spread far and wide in the community. It’s the job of contact tracers to find out about each and every one of these interactions and contact those people so they can be told about their potential exposure to the virus, the need of covid-19 testing, and then advise them to quarantine so as not to continue the spread of the virus.

Contact tracers say in many ways, they are like old-fashioned detectives.

“This really is an investigation,” said Wendy Kurlowicz, director of community environmental health at the Onondaga County Health Department. “It’s not just about gathering some information. It’s about thinking on your feet and asking the questions to make people really think honestly about where they’ve been and whom they have put at risk for exposure.”

Once someone tests positive, contact tracers need to inquire about all of the contacts the individual has had within a time period that is based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. Kurlowicz said usually, that means a few days before they started experiencing symptoms or were tested for the virus.

This investigatory work requires patience according to Tina Bourgeois, a senior licensed practical nurse and communicable disease nurse at the Oswego County Health Department.

“You can’t rush them,” Bourgeois said. “I always tell them take your time and think through this; let’s figure this out and protect everybody you’ve come in contact with — right down to the mailman.”

That said, Bourgeois said it’s more of a conversation than an interrogation. Her colleague Jodi Martin, the supervising public health nurse for preventive services at the Oswego County Health Department, agrees.

“You have to build a bond and a relationship in a short period of time or they will not be open with you,” Martin said.

That begins and ends, she says, with displaying empathy. Sometimes, the contact tracer is the first person to inform the individual that their test for COVID-19 came back positive, which can evoke an emotional response. Martin says it’s their responsibility to not only console these people but also walk them through what happens next and what to do if they become seriously ill. It also means ensuring they feel supported by asking if they have the resources necessary to last them through the period of quarantine, which is supposed to be observed for 14 days. One time, Martin and her colleagues actually delivered toilet paper and aspirin to someone who lived alone.

Bourgeois and Martin, who have spent years working in contact tracing for the Oswego County Health Department, say that COVID-19 is in some ways easier to investigate than other communicable diseases.

Everyone is familiar with what the disease is, so there isn’t as much to teach as with other diseases, and the number of potential contacts per person are somewhat limited since most people have been quarantining since mid-March.

But the sheer volume of people who have contracted the disease multiplied by the number of contacts each one has had is overwhelming county health departments across the country. Onondaga, Oswego, and other counties have had to pull employees from different divisions of their health departments just to help make these calls. As a result, many contact tracers like Kurlowicz are doing this for the first time ever.

“From nurses to the environmental health team to early intervention to public health coordinators — this is a completely different role and we jumped right into this,” Kurlowicz said. “It’s all hands on deck here.”

Even more people will be joining the team in the coming months thanks to a new state initiative. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said the state plans to build an ‘army’ of contact tracers — anywhere from 6,400-17,000 depending on the projected number of cases of COVID-19.

The effort is being funded by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the curriculum to train and certify individuals to become contact tracers is being developed by the Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health. Gov. Cuomo says ramping up the number of contact tracers is vital as the state attempts to end the statewide quarantine.

Martin said she was skeptical at first about adding people who are not public health employees to the team of contact tracers. But she does not see another way for New York’s existing staff to stop the massive amount of known people who are positive or have come into contact with someone who is positive from inadvertently infecting others, which is key to reopening safely. In fact, she encourages people to apply because the work is so vital and fulfilling.

“Sometimes, you don’t always see the benefit right there of a contact tracer, but there is a benefit,” Martin said. “You’re not going to see it because the whole purpose of that is to stop more cases, so even though sometimes you may feel like why am I doing this – they are doing a lot of good. It is rewarding.”

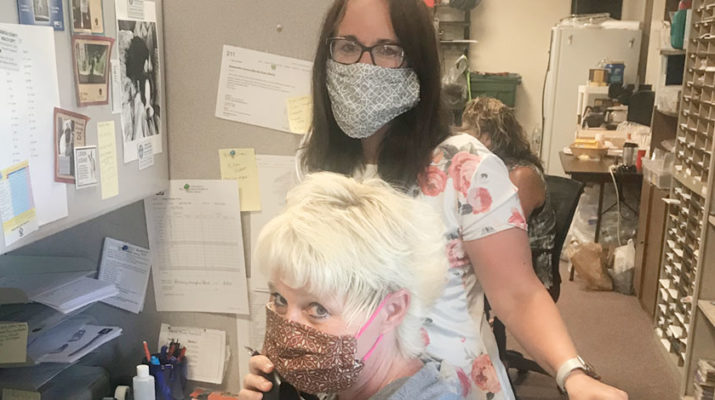

Photo: Tina Bourgeois (seated), a senior LPN and communicable disease nurse at the Oswego County Health Department, and Jodi Martin, the supervising public health nurse for preventive services at the Oswego County Health Department. They both work as contact tracers in Oswego County.