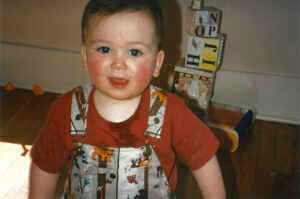

Kevin Denzak was 3 when he was diagnosed; he is now 28

By Mary Beth Roach

Denise and Joe Denzak of Syracuse, whose son, Kevin, was diagnosed with autism about 25 years ago, talk about their journey and what they see for the future for their son and for the young families receiving a diagnosis today.

Kevin Denzak was just 15 months old when Joe and Denise started noticing significant and frightening changes in his behavior. He was rocking back and forth; he was banging his head on his crib; he would hold his shoes by their laces and swing them in front of him; his complexion had turned beet red; and he had a glassy-eyed look. And these changes came about suddenly, Denise said.

Neither his fraternal twin, Brian, nor his older brother, Jordan, exhibited any of these behaviors.

One pediatrician in their group of doctors had mentioned the possibility of autism, but another in the group didn’t agree with that opinion. However, Kevin had speech delay, so he qualified for services through the Onondaga County Early Intervention Program.

At the age of 3, Kevin was finally evaluated and the Denzaks got the official diagnosis that their son was on the spectrum.

As they left the appointment, Denise recalled getting several sheets of paper, one being an explanation of what autism was and another showing various statistics, including one that said 80% would live in an institution by adulthood.

That their son might end up in a facility was devastating to Denise and Joe.

Today, Kevin is 28 years old and the transition into adulthood has “gone fairly well,” according to Denise.

“It’s challenging because he sees his peers moving on, getting married, having kids and in many cases moving away. He is still trying to figure out what his future will be,” she explained. “The biggest autism symptom we see is anxiety. If we could rid him of that, there would be no stopping him!”

“It’s challenging because he sees his peers moving on, getting married, having kids and in many cases moving away. He is still trying to figure out what his future will be,” she explained. “The biggest autism symptom we see is anxiety. If we could rid him of that, there would be no stopping him!”

He lives with his parents on Onondaga Hill. He graduated from Westhill High School and then magna cum laude from Onondaga Community College. He refers to himself as a “glass artist,” since he creates decorative pieces from fused glass.

He’s a volunteer at Helping Hounds and the YMCA; is the bingo caller at the Town of Onondaga Senior Center; is proficient in American Sign Language; and wants to find time to help at the CNY Food Bank. He has a personal trainer at the Y and proudly stated that he can deadlift 275 pounds.

But to get to this point, it has been a 20-plus year trek for the family.

This period has been marked by countless appointments with doctors and specialists, often with conflicting opinions on treatments and causes. There have been many tears, days of frustration and nights without sleep. They balanced Kevin’s needs with spending time with their other boys.

During the earlier years, Joe had to travel for work and Denise was left to face the daily challenges by herself. When the boys were younger, neither Joe nor Denise had extended family nearby to help out, although Denise’s sisters would visit when they could.

Compounding the situation were myriad food allergies and stomach and intestinal issues that Kevin endured.

Some research has indicated that there is a connection between food-related issues and children with autism spectrum disorder.

Early on, it was suggested to the Denzaks that they take him off dairy. That redness and the glassy-eyed look went away after a couple of weeks. He suffered from ringworm when he was about 5 and before he even reached his teenage years, he was diagnosed with colitis. Drastic changes to his diet have since alleviated many of these issues.

But the family had — and continues to have — a tremendous support network, including Kevin’s teachers and special education staff at his schools, including Tammy Phillips, who was a teaching assistant at Jowonio, an inclusive school for typical children and those with special needs. On Friday nights, Phillips would babysit, giving Joe and Denise needed respite.

Those Friday nights were vital and much anticipated throughout the week, Denise said.

“Even if it was just [a trip] to Target, it was a break that we knew was coming,” she said.

When Kevin was 3, he attended the Bernice Wright Child Development School at Syracuse University. Staff there helped the Denzaks get into Jowonio. For kindergarten, the boys were enrolled in the Westhill School District, where Kevin was able to get one-on-one instruction.

Phillips became a special needs teacher for Kevin in the Westhill District.

The programs and individualized attention made a significant difference, Denise believes. In addition, she said the fact that he could go through school with the same kids provided him a consistency that was especially beneficial.

“For him it was fantastic,” she explained. “Those kids stayed with him and supported him. The kids that were coming to his birthday party in kindergarten were high-fiving him at graduation.”

Over the past two decades, Denise has become a strong advocate for Kevin and in turn, for other families facing this diagnosis. She has read extensively and done research. She has attended conferences on autism. She has been persistent in seeking out specialists and securing appointments. She was not afraid to question the opinions of some of the doctors she met. She became active on Westhill’s Special Education Committee. Today, she gives presentations and offers support to younger parents.

Looking ahead, Denise said she would like to see a greater focus on research into the actual causes.

“They talk about what isn’t causing it, but I never hear real research to prevent it from happening to families. We deal with it when it arises,” she said.

For those children who are on the autism spectrum, the future might be difficult to ascertain.

The spectrum is so wide, Phillips explained. While some adults cannot hold down jobs, live with relatives or go to assisted living. However, others, who are high functioning have jobs and families, she said.